Jen Wiss-Carline is a speara and keen coastal forager. In this series of posts, she shares some tips on how to make the most of the free food waiting to be found along our shores.

In my previous posts, I’ve introduced foraging on the coastline and what you can find along the seabed at low tide. Now I hope to inspire you to take your foraging to the next level by exploring the shallow waters. If you’re willing to put on a wetsuit, snorkel, mask and fins, more impressive species await you, with many attainable from close to the surface. In fact, if you’ve ever considered spearfishing, this is a great stepping stone into the sport.

Venturing out just a little way, you can find lobsters, crabs, spider crabs (large and the easiest of all), octopus and kina – all beautiful fresh food to fill both your table and freezer. Safety rules first: don’t go out alone. Even if you’re not planning on diving down, always have a buddy with you in case you get into trouble.

Regulations

Be sure to read my first post in this series which covers regulations on coastal foraging. In particular, there are regional minimum sizes for lobsters, crabs, crawfish and the like, to ensure these species have the chance to breed before they are harvested.

Gear

I’ve written a longer guide to my recommended foraging gear here. Not all of this gear is essential but you will find it allows you to stay in the water more safely and for longer, and to search under the surface for the best finds.

A mask, snorkel and underwater torch are all essentials – these will allow you to comfortably explore below the surface without having to dive.

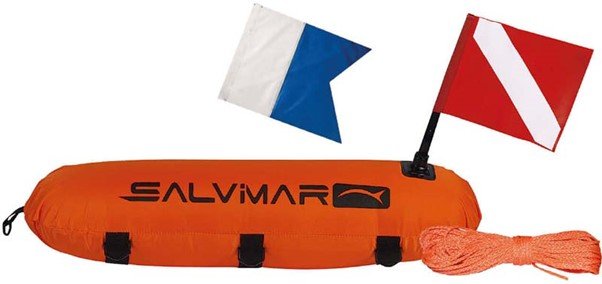

A float is also an absolute must: not only is this handy for attaching your catch bags, but most will have a surface marker (e.g. a flag) to make you visible to others such as boats in the water – a really important safety consideration.

You’ll also be surprised at just how much difference a cheap pair of plastic fins will make to your experience. Swimming with your feet alone is pretty slow and laborious – you’ll get nowhere fast. Fins give you more speed and control, so you’ll have a more successful day and they’ll help you to stay safer.

Other items I recommend include a wetsuit, gloves and socks, a knife, belt and dive weight. Each of these has their uses: whether safety or protection.

A gauge is also a handy bit of kit, whether you’re foraging on the shore or in the water. It allows you to check the size of your catch and ensure it meets legal limits. You’ll typically be measuring the carapace, which I’ve explained with some diagrams in my post here. Finally, there are a host of gadgets such as hooks and gaffs that can help you tease stubborn crustaceans from their holes while keeping your fingers away from their nippy claws.

Crabs

Brown/edible

To find brown / edible crabs you want to be looking under the seaweed for little caves, cracks and holes. These tasty critters will often be sleeping tucked snuggly into a tight crack. You best chance is your first chance while they are still slumbering. You’ll need a hook or gaff to slide behind them to quickly work them out. Once extracted, hold them by their back legs where their claws can’t reach you. A waterproof torch will serve you very well in your quest for finding these.

Most by-laws put the minimum size for their carapace (the distance across the longest part of their body) at around 160mm for male and 150mm for female, so leave small crabs where you find them.

Spider crabs

Spider crabs are such a great catch, given how large they are. In summer, they venture into the shallow water to breed and you’ll find them walking around in the open or in piles reproducing, which makes them a very easy target. Look for the males with their fatter claws as these have more meat and are less hassle to clean and cook. Grab them, tip them onto their backs and they’ll just curl up and fall asleep – easiest dinner ever. The minimum size is typically 130mm for the carapace.

Lobster

Lobsters are your ultimate goal: they cost a fortune in supermarkets and restaurants, but they’re fresher and free from the sea! The best months to find them are May to October.

In the UK they are dark blue – the red colour you are probably expecting comes from cooking.

To find lobsters, you’ll need to be comfortable diving down, although you don’t need to go more than a few metres (remember, don’t go alone). You’ll need to explore all the holes and cracks amongst the kelp, using your torch for guidance. When you find one, mark the spot with your torch and return to the surface. Spend some time catching your breath so you’re comfortable and can maximise your breath hold.

When you dive again, put your hook over the lobster’s back and between its legs, then quickly hook it out. Lobsters are really fast so you need to grab them quick on their back, above the tail and clear from the claws.

The minimum size is typically 90mm for the carapace and also be aware that you MUST release any lobster that has a V cut into its tail, or has eggs underneath.

Octopus

Octopus also like hiding in holes and you’ll need your torch to find them, together with a gaff hook to get them out. Minimum sizes are usually around 750g but aim for bigger as they won’t usually have started to breed at that weight. They are intelligent creatures and you should dispatch them quickly and humanely by stabbing them between the eyes.

Kina

You’ll find the larger kina in the water along rocky reefs, growing up to 15cm. These are best foraged in season (with the spring bringing them on), as it makes a huge difference to their taste. They are eaten raw and must be caught alive. Crack them open with a knife, shake out the guts and eat the remaining colourful yellow or orange roe.

You can find more tips on foraging crabs, lobsters and octopus here.

All images licensed through Envato.