Spring is well and truly sprung and the perennial weeds are popping up everywhere, much to the disgust of proud gardeners and allotment owners. A lot of the weeds have medicinal and edible uses, but some are better than others, and frankly some of them are little more than wild salad “fillers”. However, there’s one particular genus/group of prevalent weeds with medicinal qualities, nutritional benefits and they actually have a taste worth looking for too. It’s the plantain herb (genus Plantago), also known as fleaworts.

As the title suggests, I often find myself saying “it’s not related to the banana-like vegetable which you see at the supermarket”.

Species

At the last count there were about 200 species in the genus, but I tend to stick with wide-spread, UK-based varieties such as Broadleaf (Plantago major), Ribwort (Plantago laceolata) and occasionally Sea (Plantago maritima) and Buckshorn (Plantago coronopus); All of which have very similar properties and uses. They all have slightly different seasons, with Broadleaf tending to pop-up first, then Ribwort a little later, and Buckshorn and Sea Plantain from about mid-summer; As with all of these things, it depends upon your location, and the current weather conditions.

Identifying plantain

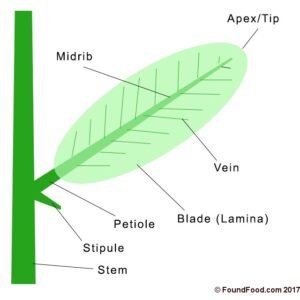

It’s easy to ignore and walk all over, because it is a very common weed, and without its flower heads it blends into the grassy background easily; But once you’ve learnt to recognise it, you’ll see it everywhere. Whilst the basic leaf shapes may vary (Broadleaf has wide, round leaves; Ribwort has long, strap-like leaves), there are some features that they all have in common:

- Parallel leaf veins – The leaf veins run from base to tip and are usually easy to see. If you’re really careful, you can tear a leaf and the ribs can stay attached so you have two halves of a leaf attached by threads.

- Flower spike – They all send up a long flower spike with tiny veins.

Eating plantain herb

General rules of foraging withstanding (look for potential contamination, condition, wash it, etc.), plantain leaves, stalks and flower heads can be eaten raw – and this is where the surprising taste comes through. At first, it’s a bit of a plain “green” taste, but give it a good chew, get your juices flowing and get it to the back of your mouth and… Mushrooms. If you’ve never tried Plantain before, you really have to give this a go; I promise you won’t be disappointed. The most intense flavour seems to come from the flower heads (they’ll be out in a few months’ time), but the leaves give the same flavour too.

Recipes

Crisps

A very quick and easy snack. Wash and dry your plantain leaves (I find that broadleaf works best for this) and put them into a shallow pan of hot oil. Don’t overcrowd the pan or they’ll just wilt and not crisp up. Give them up to 30 seconds, turning once if necessary, then drain and eat as a nice little snack. They can be salted while they’re cooling too, if you like.

Vodka

This was a mad idea I had one day of getting an earthy, mushroom flavour into cocktails. Leaves and seeds infused in vodka for 3 months, then strained. The earthy flavour counterbalances sweetness, but I find a little bitterness really lifts it. So mixed with nettle cordial for the sweetness, a few splashed of home-made bitters (or Angostura), and topped with tonic water works well.

Plantain herb and garlic mustard risotto

This is your full recipe for this issue. Apart from the fact that it makes a really good flavour, I’ve sold this idea to learner foragers who are scared of mushroom picking – It means that you can have a mushroom and garlic risotto with no mushrooms or garlic!

Ingredients

- 2 tbsp oil

- 1 large white onion

- 4 large handfuls of plantain herb leaves, stalks and flower heads

- 2 litres of water (to make 1 litre of stock)

- 250g Risotto rice

- 1 handful of garlic mustard leaves

Method

- Put 2 handfuls of leaves, stalks and flowers in a couple of pints of water, bring to the boil and simmer for at least 1 hour. Allow to cool and strain out the plants. Add the remaining fresh plants and simmer again for 1 hour, then strain.

- If the stock isn’t already reduced to 1 litre, simmer it again to reduce.

- Fry a chopped onion in a little oil until golden.

- Add the risotto rice and toss in the onion and oil.

- Add a little plantain stock and stir until it is soaked up.

- Repeat until the rice doesn’t soak up the stock any more, then put the rest of the stock in.

- Keep on a low heat until all the stock is gone and the rice is thick and sticky.

- Remove the risotto from the heat and stir your sliced garlic mustard leaves through.

NOTE: Garlic mustard leaves can have a very bitter after taste but cooking them can kill the gentle garlic flavour. We stir them through at the end like this, because a little heat tames the bitterness without destroying the garlic flavour.

Health benefits

Plantain has a long history of being used in traditional herbal medicine, and for very good reason. Modern investigations have shown most traditional uses are actually highly effective.

Plantain is “mucilaginous” which means that it has a soothing effect on both the skin and the mucous membranes, so it is an effective relief for burns, bites and stings, as well as on coughs, sore throats, and urinary tract infections. I’ve found that it is best used as a fresh, first-aid herb for burns, bites and stings – you can crush the leaves with a little water and apply directly; If it’s for me, I’ll chew them with a little spit and apply it. For internal injuries or issues, you can make a tea from either fresh or dried herb. Just pour hot water over the leaves and allow to infuse for 10 to 15 minutes. As well as mucilage and its soothing, anti-inflammatory ability, studies have found that Plantain contains allantoin, a substance proven to stimulate the regeneration of tissues for healing, and aucubin, with proven antibiotic actions.

Summary

To native Americans, this was known as “White man’s footprints” because it spread wherever the European settlers went. Apart from kids using it as an improvised gun, or the species Plantago psyllium used for improving digestive transit, this little weed gets largely ignored; I hope that after reading this, you’ll realise its amazing food and medicine benefits and make good use of it.

Originally published in The Bushcraft Journal Issue 25 - 2019