Winter is upon us, the frosts have started already and it’s tempting to wrap up warm and stay indoors, but there’s still a whole world of food to be had out there. For this article I want to pick on a commonly used plant that seems to not get much use outside of making booze. I am of course talking about the humble Sloe of the Blackthorn bush (Prunus spinosa).

I’m not going to dive into recipes or variations for sloe gin, Epine aperitif, or even sloe wine (another of my favourites). After all, it’s very simple and there are tons of recipes out there already; not to mention that you can now buy sloe gin off the shelf (and I won’t start on all the reasons why that’s wrong!).

Species

Blackthorn is a member of the Rose family and like most fruit of the Rosacea, it has seeds/stones containing compounds which can convert to hydrogen cyanide in the stomach, however you’d have to consume a lot of the seeds for it to affect you, and we’re discarding the stones today anyway; It’s that hydrogen cyanide compound that gives almonds their flavour, and which comes out in sloe gin if it’s infused for a long time. Trust me, it’s a good thing.

Identifying Blackthorn

Blackthorn grows in dense tangled bushes, with evil black spikes up to a couple of inches long, so when picking the berries it’s best to wear suitable clothing or be very careful. If you’re looking to identify it in spring Blackthorn and Hawthorn can have very similar flowers and spikes, but where Blackthorn flowers before its leaves appear, Hawthorn flowers after its leaves have appeared. If the leaves are out it’s much easier. Blackthorn has simple small leaves, Hawthorn has lobed leaves.

Eating Sloe Berries

As you probably know already, sloes are a wild plum but are incredibly sour and astringent until they’ve been frozen. Whether by the natural frosts or by putting them in the freezer for a day or two, the freezing process releases more of their natural sugars and makes them much more palatable for our infusions. A few years ago, I was licking my fingers after preparing some berries for wine and it struck me that now they’re nice and sweet, why not use them like a normal plum?

Sloe Dumplings

This is your recipe for this issue. I adapted it from a family recipe which used shop bought plums, which was lovely but I think that these small snack size versions are even better:

Ingredients

- 12 frozen sloes

- 1 tbsp caster sugar

- 125g peeled potatoes

- 20g butter unsalted

- 50g breadcrumbs

- 20g granulated sugar

- 1 egg

- 60g plain flour

- Pinch salt

- Pinch cinnamon

Method

- Put your potatoes on to boil. You want it nice and soft, like your going to make mash.

- Clean your sloes and make sure that they’re defrosted. Remove the stones keeping as much of the flesh as possible. Sprinkle the caster sugar over the sloes.

- Melt the butter in a pan and add the breadcrumbs. Cook gently until golden brown then remove from the heat. Stir in the granulated sugar thoroughly and set aside to cool.

- When the potatoes are done and cool enough to handle, shred them into a bowl – I just mash them with a fork.

- Add the egg, salt, cinnamon and flour and mix into a sticky dough. If it’s too wet add a little more flour.

- Get a pan of water on the boil.

- Take a small piece of dough at a time, flatten it into a 5mm thick circle. Add the sloe, fold the dough and shape into a ball.

TOP TIP: If you find the dough too sticky to mould in your hand, wet your hands; It makes it much easier. - A few at a time, drop the dough balls into the simmering water and cook until they rise to the surface.

- Remove using a strainer to drain excess water and put straight into the breadcrumbs. Roll them around so they’re coated and leave to cool.

- Serve the dumplings cold, maybe with custard or a little Sloe port.

Health Benefits

Sloe berries are rich in Vitamin C and Vitamin E, and also have concentrations of potassium, calcium and magnesium. They’re also packed with antioxidants, phenols and essential fatty acids, all of which are good for maintain health and reducing the likelihood of chronic disease.

Summary

When we’re looking at foraged food it is sometimes easy to stick with what we know, even making small changes to recipes, and we often overlook the basic nature of a thing. Sloes are wild plums and we know that they sweeten up when frozen and defrosted, so why not use them as tiny plums? OK, so they’re a little fiddly, but I think it’s well worth the effort. I can promise you that they make lovely desserts, sweet and sour sauces, and this year why not try a lovely rich sloe sauce to go with your Turkey?

Spring is well and truly sprung and the perennial weeds are popping up everywhere, much to the disgust of proud gardeners and allotment owners. A lot of the weeds have medicinal and edible uses, but some are better than others, and frankly some of them are little more than wild salad “fillers”. However, there’s one particular genus/group of prevalent weeds with medicinal qualities, nutritional benefits and they actually have a taste worth looking for too. It’s the plantain herb (genus Plantago), also known as fleaworts.

As the title suggests, I often find myself saying “it’s not related to the banana-like vegetable which you see at the supermarket”.

Species

At the last count there were about 200 species in the genus, but I tend to stick with wide-spread, UK-based varieties such as Broadleaf (Plantago major), Ribwort (Plantago laceolata) and occasionally Sea (Plantago maritima) and Buckshorn (Plantago coronopus); All of which have very similar properties and uses. They all have slightly different seasons, with Broadleaf tending to pop-up first, then Ribwort a little later, and Buckshorn and Sea Plantain from about mid-summer; As with all of these things, it depends upon your location, and the current weather conditions.

Identifying plantain

It’s easy to ignore and walk all over, because it is a very common weed, and without its flower heads it blends into the grassy background easily; But once you’ve learnt to recognise it, you’ll see it everywhere. Whilst the basic leaf shapes may vary (Broadleaf has wide, round leaves; Ribwort has long, strap-like leaves), there are some features that they all have in common:

- Parallel leaf veins – The leaf veins run from base to tip and are usually easy to see. If you’re really careful, you can tear a leaf and the ribs can stay attached so you have two halves of a leaf attached by threads.

- Flower spike – They all send up a long flower spike with tiny veins.

Eating plantain herb

General rules of foraging withstanding (look for potential contamination, condition, wash it, etc.), plantain leaves, stalks and flower heads can be eaten raw – and this is where the surprising taste comes through. At first, it’s a bit of a plain “green” taste, but give it a good chew, get your juices flowing and get it to the back of your mouth and… Mushrooms. If you’ve never tried Plantain before, you really have to give this a go; I promise you won’t be disappointed. The most intense flavour seems to come from the flower heads (they’ll be out in a few months’ time), but the leaves give the same flavour too.

Recipes

Crisps

A very quick and easy snack. Wash and dry your plantain leaves (I find that broadleaf works best for this) and put them into a shallow pan of hot oil. Don’t overcrowd the pan or they’ll just wilt and not crisp up. Give them up to 30 seconds, turning once if necessary, then drain and eat as a nice little snack. They can be salted while they’re cooling too, if you like.

Vodka

This was a mad idea I had one day of getting an earthy, mushroom flavour into cocktails. Leaves and seeds infused in vodka for 3 months, then strained. The earthy flavour counterbalances sweetness, but I find a little bitterness really lifts it. So mixed with nettle cordial for the sweetness, a few splashed of home-made bitters (or Angostura), and topped with tonic water works well.

Plantain herb and garlic mustard risotto

This is your full recipe for this issue. Apart from the fact that it makes a really good flavour, I’ve sold this idea to learner foragers who are scared of mushroom picking – It means that you can have a mushroom and garlic risotto with no mushrooms or garlic!

Ingredients

- 2 tbsp oil

- 1 large white onion

- 4 large handfuls of plantain herb leaves, stalks and flower heads

- 2 litres of water (to make 1 litre of stock)

- 250g Risotto rice

- 1 handful of garlic mustard leaves

Method

- Put 2 handfuls of leaves, stalks and flowers in a couple of pints of water, bring to the boil and simmer for at least 1 hour. Allow to cool and strain out the plants. Add the remaining fresh plants and simmer again for 1 hour, then strain.

- If the stock isn’t already reduced to 1 litre, simmer it again to reduce.

- Fry a chopped onion in a little oil until golden.

- Add the risotto rice and toss in the onion and oil.

- Add a little plantain stock and stir until it is soaked up.

- Repeat until the rice doesn’t soak up the stock any more, then put the rest of the stock in.

- Keep on a low heat until all the stock is gone and the rice is thick and sticky.

- Remove the risotto from the heat and stir your sliced garlic mustard leaves through.

NOTE: Garlic mustard leaves can have a very bitter after taste but cooking them can kill the gentle garlic flavour. We stir them through at the end like this, because a little heat tames the bitterness without destroying the garlic flavour.

Health benefits

Plantain has a long history of being used in traditional herbal medicine, and for very good reason. Modern investigations have shown most traditional uses are actually highly effective.

Plantain is “mucilaginous” which means that it has a soothing effect on both the skin and the mucous membranes, so it is an effective relief for burns, bites and stings, as well as on coughs, sore throats, and urinary tract infections. I’ve found that it is best used as a fresh, first-aid herb for burns, bites and stings – you can crush the leaves with a little water and apply directly; If it’s for me, I’ll chew them with a little spit and apply it. For internal injuries or issues, you can make a tea from either fresh or dried herb. Just pour hot water over the leaves and allow to infuse for 10 to 15 minutes. As well as mucilage and its soothing, anti-inflammatory ability, studies have found that Plantain contains allantoin, a substance proven to stimulate the regeneration of tissues for healing, and aucubin, with proven antibiotic actions.

Summary

To native Americans, this was known as “White man’s footprints” because it spread wherever the European settlers went. Apart from kids using it as an improvised gun, or the species Plantago psyllium used for improving digestive transit, this little weed gets largely ignored; I hope that after reading this, you’ll realise its amazing food and medicine benefits and make good use of it.

Originally published in The Bushcraft Journal Issue 25 - 2019If you’ve been around foragers in winter, or been reading about it, or been foraging yourself, the chances are that you’ve come across the expression “bletting“; But what does it actually mean?

Simple definition of bletting

Well, at its simplest it’s a stage of fruit development in-between ripening and rotting. It describes when a fruit has fully ripened, has started to break down, but is not quite rotting yet. There’s a bit of semantics at play here, strictly speaking bletting is actually the early stages of rotting, but before the fruit goes bad.

What does it really mean?

For certain fruit, bletting is actually an essential process to make it edible for us. Fruit such as Sloes (the fruit of the Blackthorn bush – Prunus spinosa) and Medlars (Mespilus germanica) for example, are quite sour and astringent when ripe. Leave them to “blet” a little and the cell walls begin to break down and release sugars, thereby sweetening the fruit. Rosehips (Wild dog rose – Rosa canina) are often rock hard until they’ve begun to blet, at which point you can squeeze their citrus-like juice out with your fingers. For fruit such as Sloes, it was always recommended that you wait until after the first frost to pick them, as the frost creates ice crystals in the flesh which has the same effect as bletting; However, nowadays with our changing seasons and modern technology, it’s much simpler to pick them as soon as they’re ripe and put them in the freezer!

So, “Bletting”. An odd word, a simple yet important process, and nature’s way of helping us to have more food to eat.

I recently stayed on the East coast of Corfu (Greece) for a week, and whilst the intention was to have a week of complete relaxation, I don’t think it’s possible for a forager to ignore plants, ever.

Anyway, I was pleased to see so many plants that I recognised from foraging in the UK, but there were also plenty that I wouldn’t have a clue about – that’s where some local knowledge would help if I intended to stay there and forage!

Quite often on foraging walks, we get onto the subject of lost knowledge, and how in other parts of the world (including some of mainland Europe) they don’t have “foraging” because gathering wild edible plants is just part of life. However, whilst it was encouraging to see some evidence of wild food gathering, it was also clear that the practice is beginning to die out in Corfu too.

Horta forager

In Greece, they have a dish called “horta” which just means greens and will probably have different contents from one restaurant to another. It can include dandelion leaves, amaranths, mustards and chicory. Interestingly, the Greek for vegetarian is hortafagos which translates as “weed-eater”. Anyway, it was encouraging to see that you can still buy horta, gathered by a local forager, from the markets.

Slightly less encouraging was the amount of perfectly good olives, grapes, prickly pears and other edibles rotting on the plants, or on the floor beneath them.

Edible plants in common with the UK

So what can you recognise their from your foraging here? I’m sure that there is plenty more, but this forager saw:

So, we all know (or should know) that every part of the Yew tree is highly toxic to humans. When I say highly toxic, what I mean is that a very small amount can kill you. All parts contain taxin, a complex of alkaloids which are rapidly absorbed.

If you are poisoned by it, sometimes there are no symptoms, followed by death within a few hours. Where there are symptoms, they include trembling, staggering, coldness, weak pulse and collapse.

So what’s the good news?

Now that I’ve scared the living daylights out of you, there is one part that is not toxic. See those pretty little red berries, the red flesh is not toxic, and is also quite nice and sweet tasting; However, the hard, dark-coloured seeds inside, have probably the highest concentration of toxins of the whole tree. It is said that if unbroken, the seeds will pass through you without being digested and without causing harm.

I’m not sure it’s worth the risk, personally. However, I have been known to pick a few and spit the seeds out. The flesh is really quite nice (although I have heard some people compare the texture to snot – but I couldn’t possibly comment).

I’m assuming that it’s for for safety’s sake that there are no recipes for yew berry flesh, or even many instructions to tell you the safe way of eating them. After all, I could easily imagine someone seeing other people eating them and assuming that they’re completely safe, followed shortly afterwards by a trip to the hospital, or the morgue!

Time to make some yew liqueurs

That said, I decided that I would have a play with the flavours and some spirits to see if anything gave good results. Maybe some kind of yew liqueur?

The first step is to separate the flesh from the poisonous seeds. I tried to freeze them first to make it easier, but they didn’t freeze very well, so it was a quite disgusting manual job. The squeezed flesh went quite sticky.

So finally, I split the berry flesh into three portions and put them into some clean, sterilized Kilner-type jars. Over each, I then poured filtered white rum, filtered gin, and filtered vodka. Then I left them to sit and infuse (hopefully), giving them a helpful little shake each time I passed by.

The results…

So, after infusing for 2 weeks now, so it was time for a little try. At this point, the spirits had started to sweeten slightly, but not much change to colour or flavour.

After 4 weeks, things had moved on somewhat, so I strained and bottled the infusions.

Now you can see that not only have they taken on slightly different colours across the different spirits, but also I’ve ended up with slightly different amounts of end product, despite the fact that they started with the same volume of berries and spirits.

The judgement

First of all, they are all quite nice. The berries have imparted a slight sweetness, some of their stickiness has come through and made the spirits thicker and smoother, and there’s a very subtle citrus berry flavour.

However, one stands out above the rest. The Gin infusion seems to have worked very well. It’s nice to drink on its own, and if we hadn’t drunk it all it would probably go quite well in a cocktail. Maybe I’ll make it again this year, but try to save some for cocktail experiments, or make some more!

I was out for a wander in deepest Essex recently and I came across a patch of land where Wild Carrots (Daucus carota) seem to thrive. You can barely take a few steps without tripping over some.

Anyway, I wasn’t entirely prepared, but I did a quick video on my phone so I could show them…

Hairy Bittercress

I ended up gathering quite a few, along with some hairy bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta). The bittercress tastes exactly the same as cress that you might buy from a supermarket (although all the sweeter for being free!).

Wild Carrots

What to do with these diminutive, white carrots?

Firstly, the smaller, younger ones can be eaten raw (and I did), and they make a really nice, sweet snack.

Next, I quickly boiled a couple of the larger, tougher ones. Unsurprisingly, they tasted just like supermarket carrots, but somehow better.

Then I chopped a few of the roots and some of the leaves into a salad, which was served with a spaghetti Bolognese (which also had a few wild carrots in it).

Finally, I now have a handful of roots macerating in Vodka. I’m hoping that the sweet carrot smell and taste are going to come through.

One for the future, some kind of foraged carrot-cake?

I was out for a walk around the Lee Valley last night, particularly looking out for Elderberries and Yarrow for some home-brewing projects I have planned. I found what I needed, but I could help also noticing the huge amounts of pink flowering Himalayan Balsam along the river’s edge just about everywhere.

Whilst it looks very pretty, it’s a controversial plant as it’s the invasive immigrant, Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera). It is highly invasive, and tends to choke up rivers quite quickly.*

It does this with an amazing seed spreading system, which involves the seed heads ‘exploding’ and flinging the seeds up to seven feet away.

However, there is a positive aspect to this plant. Most of it is edible, and being in such abundance and widely hated, there is no reason not to collect some (carefully) and cook it up!

*Himalayan Balsam and the law

I’ve been asked by the Non-native Species Inspectorate, quite rightly, to point out that the transportation of seeds or whole plants of Himalayan Balsam is an offence under the Invasive Alien Species (Enforcement and Permitting) Order 2019 in England and Wales and Section 14AA of the Wildlife and Countryside Act in Scotland. This means that no seeds or plants should be removed from the site where they currently grow, and sowing seeds or planting elsewhere either deliberately or accidentally would be a particularly serious offence.

So in other words, pick it and eat it/use it where it grows, and don’t take it somewhere else!

Himalayan Balsam Recipes

A quick internet search for “Himalayan Balsam Recipes” will turn up plenty of results for you. I won’t copy them here (unless it’s to review them after I’ve given it a try), but some of the things I’ve seen include:

- Champagne (Flowers)

- Wine (Flowers)

- Curry (Seeds)

- Using the stem as a straw for drinks

- Preserve (Flowers)

- Falafel (Seeds)

Introduction to a foraging definition

I wanted to post something along the lines of a definition of foraging and what it means to me, but I am in no way an absolute authority, hence it’s more of a discussion point rather than a hard and fast definition. This is what it means to me, but I’d love to hear from readers about their opinions.

Why made me think of this

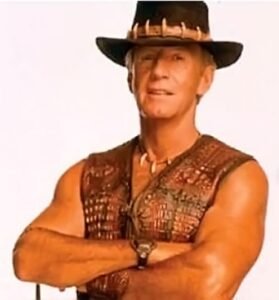

The incident that spurred this, was a night in with my wife, watching an old favourite film on the TV – Crocodile Dundee. Early on in the film, Sue is in the bush with Mick Dundee and he’s prepared a spread of “bush tucker” for her to eat. This spread included fire-roasted goanna, yams, witchety-grubs, fire ants. etc.

Sue says to Mick “What about you. Aren’t you having any?”

Mick replies “Me?” and gets a tin out of his bag.

“Well, you can live on it, but it tastes like shit.”

Categorisation

That had me thinking that there’s actually two types of food foraging:

- Foraging for survival.

- Foraging for everyday consumption.

Where foraging for survival is all about calorie intake regardless of flavour/texture/palatability; and foraging for consumption is about finding wild food which is pleasant on it’s own, or which adds to the palatability of everyday meals/snacks.

Foraging for survival might include such things as cat-tails rhizomes and silverweed roots for carbs/calories, ground elder, nettles, etc for teas and their nutrients.

Foraging for everyday might include things such as blackberries, raspberries, red-currants, hazelnuts, wild garlic and so on for their flavours.

Other considerations

You could possibly include a third option of “Foraging for the study of Ethnobotany” to the foraging definition, where Ethnobotany is the study of the human usage of plants. However, I would class this is something that sits alongside the other two options.

And this article doesn’t even go into foraging for medicinal wild plants (which I am also doing).

Discussion

Which category an item fits into, can be entirely down to who is doing the eating. For example, you may find the suggestion of eating woodlice completely distasteful and categorise them as survival food; on the other hand, you may enjoy their shellfish-like taste as part of a rice, potato, or bread-based dish, in which case they fit into the other category.

Whilst it’s not really possible to look at one category without the other in this foraging definition, my main area of focus is foraging for everyday consumption. So, along the way I’m also discovering survival foods, and understanding certain aspects of Ethnobotany.

As something I’ve been aware of for some time, and looking out for Linden tree (Lime) flowers in the local area; I was pleased to find a big, old Linden tree not far from where I live. And it was positively overloaded with flowers.

Just for clarification, with these trees the name “Lime tree” and “Linden tree” are interchangeable. They are not the tree which bears the lime fruit. Also, I’ve titled this Tilia x europia (common Lime) because that’s the tree I found. It’s equally applicable to Tilia platyphyllos (Large-leaved Lime) and Tilia cordata (Small-leaved, Lime).

The flowers are usually within reaching distance anyway (unless the lower branches have been trimmed), but as an added bonus, this tree was on a slope too, so a lot of branches were at waist height, for easy picking.

Identification

- Common Lime is a deciduous, broadleaf tree, native to the UK and quite common.

- The bark is pale grey/brown and has irregular ridges.

- It is quite common to find multiple shoots growing out from the base of the tree.

- Twigs are hairy and brown, but can turn reddish when in the sun.

- Leaf buds are red with two scales; one small and one large. The buds look a little like a boxing glove.

- The leaves are dark green and heart shaped, usually six to ten centimetres. The base of the leaf is asymmetrical and the underside has tufts of small white hairs at vein axils.

- The flowers are white-yellow, five petals, hang in clusters of two to five, hang from a bract, and have both male and female reproductive parts.

Uses

So why am I going on about these Linden tree flowers? Well, in the past, Linden Flowers have been used as a herbal remedy for all kinds of ailments, including high blood pressure, migraine, headaches, digestive complaints, colds, flu, insomnia, liver and gallbladder disease, itchy skin, joint pains and anxiety.

Apparently, during the war, Linden was used to make a soothing, relaxing tea. You can imagine why people might have wanted it then!

Personally, I have been known to suffer from mild anxiety, insomnia (of a kind) and joint pains, so I’ll be giving it a try (after doing my own research).

As I understand it, it also makes a nice drink, and as an occasional thing isn’t likely to do any harm

Warning

As always, you absolutely must do your own research before diving into believing the first thing you read online, and also check with your doctor too. Apparently some people have reported allergies to Linden, but apart from that Linden tea is pretty harmless stuff.

What to do with Linden tree flowers

Make sure that you pick the pale green bract that comes with the flowers – you’ll need it all. Also, pick responsibly. Whilst it’s unlikely that you could over-harvest a tree, if you need a lot, make sure you take small amounts from several trees.

Next step – either dry it for future use (in the sun on a sheet, in your oven, or in your electric dehydrator), or make a tea from it immediately.

Tea

Put a few handfuls of flowers in a pan with one to two litres of water.

Bring to the boil, cover and remove from the heat, and leave it overnight.

Strain out the blossoms and keep the infusion in the fridge for up to three days. You can drink it cold, or reheat it. You can freeze the tea to keep it for longer, or make it into an elixir (thanks to the ladies at www.handmadeapothecary.co.uk for the idea) by adding 50% spiced rum to use as a cold remedy (take 50mls in hot water and go to bed to sweat it out).

Next steps

Coming soon – I plan to make my linden tree flower tea on video…

Helper Sites

- The Forager Helper

- The Wild Herbalist Helper (coming soon…)